A primer on additionality and carbon removal

Additionality is a vital test for carbon credits, but there are several ways to improve our approach to it to better serve the budding carbon removal market

Requirements and tests for carbon projects to generate a marginal benefit over their baseline or “business-as-usual” scenarios date back to the origins of carbon markets and the concept of carbon credits. Additionality is a key feature of crediting programs that helps protect the environmental integrity of claims. However, the emergence of carbon dioxide removal raises new questions about additionality and how it should be understood and evaluated. This article argues that standards setters should maintain additionality requirements for carbon removal but increase leniency for edge cases and explore opportunities such as insetting and book-and-claim accounting to better account for the carbon negativity generated by non-additional removal projects.

Introducing Additionality

Most carbon dioxide removal (CDR) companies depend on the prospect of selling carbon credits to fund their operations. Individual credits are meant to represent the net removal of one tonne of CO2 from the atmosphere after accounting for project emissions. The purchase and subsequent retirement of credits allows buyers to compensate for or “offset” a corresponding emission of a tonne of CO2.

To ensure that the purchase of credits creates a climate impact above and beyond what would have happened anyway and justify compensatory claims, standards setters for voluntary and compliance carbon markets set what are known as additionality requirements for carbon crediting projects. The Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM), a non-profit that emerged from the Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets, defines additionality by stating, “The greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reductions or removals from the mitigation activity shall be additional, i.e., they would not have occurred in the absence of the incentive created by carbon credit revenues.” This definition comes from the organization’s Core Carbon Principles (CCPs) and associated Assessment Framework, which are used to assess and rubber stamp carbon-crediting programs (including registries) and their crediting methodologies.

There are several common categories of additionality tests, all of which have historical origins in early carbon market guidance that is discussed in the following section. One of these is financial additionality. This tests for whether a project would be profitable or not without “carbon finance,” which is just the sale of carbon credits. The thinking goes that if a project would be profitable without carbon credits, either through the sale of co-products or the use of subsidies, it is likely to proceed anyway for pure economic reasons and is therefore not additional. Another common category is regulatory additionality, which tests whether a project or its key aspects are required by law. If so, the project is likely not additional, as it would have had to occur regardless of carbon credits. Common practice tests may also be applied, which analyze whether a given project is common in a region. If it is, this implies that there are some other kinds of supports for the project, weakening the case for additionality.

When applied to emissions reduction projects, such as the use of cleaner energy or energy-efficient practices, the need for additionality to ensure true environmental benefits from crediting is clear. If an entity is going to reduce emissions anyway in a baseline scenario due to financial or regulatory reasons, then allowing a sale of that emissions reduction claim to another entity merely represents cash changing hands with no additional climate impact. This deprives emissions reduction projects that are additional from necessary funds, leading to worse climate outcomes.

The case for applying additionality for CDR projects is a bit more complicated. Emissions reduction represents not doing something (emitting), while CDR is an active, physical process that causes an observable change in the world. Non-additional emissions reductions that occur in the absence of carbon credits, e.g., a person saving money on their utility bill by putting solar PV on their roof, simply lead to lower emissions for the entity doing the project. Non-additional CDR may occur regardless of credits but still creates a net flux of CO2 out of the atmosphere as opposed to just preventing its emission in the first place. Framed in another way, if societal emissions hit zero, new reductions would not exist whereas new, non-additional CDR would still create marginal fluxes of CO2 out of the atmosphere. This categorical difference between reductions and removals suggests that non-additional removal may have more value than non-additional reductions that should perhaps be accounted for in some way as I will discuss here.

This is only one issue with how additionality is currently structured. There are several other areas where it could stand to be improved for the emerging CDR credit market. Here, I unpack the history behind additionality to explore its relevance to CDR and propose several changes that could help address some of this complexity in a manner that I hope is reasonable, fair, and scalable.

A Brief History

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) held the first Conference of the Parties (COP1) in Berlin, Germany in 1995. Delegates chose to pilot a program known as Activities Implemented Jointly (AIJ). The purpose of the program was to “enhance the transfer of technology and know-how on global warming protection from developed to developing countries and to gather experience on the opportunities and obstacles for the joint implementation of policies and measures to avert climate change.” This experience was meant to help inform the design of carbon crediting mechanisms to be outlined in the subsequent Kyoto Protocol.

The AIJ revealed core issues related to understanding emissions in baseline scenarios, also known as reference cases, to which the benefits from emissions reductions projects could be compared. Attempting to quantify the delta between emissions in the world with and without a reduction crediting project is naturally necessary for calculating the number of credits that should be issued for such a project. However, this is a difficult task as (a) it is impossible to have full knowledge of counterfactual scenarios; (b) baselines can change over time; (c) there are feedback loops between the existence of projects and the state of the world; and (d) project developers can have incentives to skew projections or even emit more to inflate future crediting.

Lessons from the AIJ helped inform the development of the Kyoto Protocol, which was adopted at COP3 in Kyoto, Japan in 1997. Article 6 from Kyoto (the OG Article 6) specifies, “any Party included in Annex I may transfer to, or acquire from, any other such Party emission reduction units resulting from projects aimed at reducing anthropogenic emissions by sources or enhancing anthropogenic removals by sinks of greenhouse gases in any sector of the economy, provided that: … Any such project provides a reduction in emissions by sources, or an enhancement of removals by sinks, that is additional to any that would otherwise occur.” Article 12 features a similar requirement.

The Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) emerged from Kyoto and functions as a UN-run carbon crediting scheme focused on allowing wealthier countries to purchase credits from less-wealthy countries in a way that ideally supports sustainable development. It operationalized the high-level additionality requirements set out in the protocol. For example, CDM standards include the CDM project standard for project activities, which notes in section 7.5.4 that “The project participants shall demonstrate … that the anthropogenic emissions of GHG by sources are reduced below those that would have occurred in the absence of the proposed CDM project activity.”

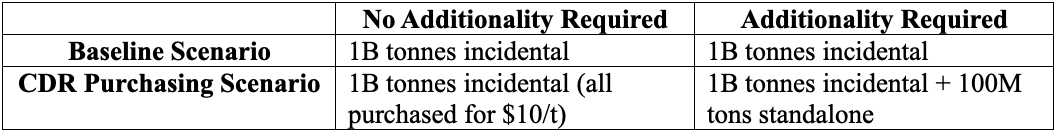

Another standard document, CDM validation and verification standard for project activities, provides a deeper explanation of how entities managing crediting should approach validation and verification of additionality for projects via investment analysis, barrier analysis, and common practice analysis. These concepts are further explored in companion documents including the Tool for the demonstration and assessment of additionality, Combined tool to identify the baseline scenario and demonstrate additionality, Methodological tool - Investment analysis, Guidelines for objective demonstration and assessment of barriers, and Methodological tool - Common practice.

Standards developed for the voluntary carbon market in the early 2000s were heavily influenced by those set for the CDM. Additionality requirements are present in high-level methodology/protocol standards set across the “big four” registries: Verra, Gold Standard, Climate Action Reserve, and ACR. Standards for more modern, CDR-focused registries including Puro and Isometric also incorporate additionality requirements. The profusion of this requirement across voluntary carbon market registries is also incentivized by its presence in ICVCM and ICROA requirements that are necessary for rubber stamping by these organizations and the associated legitimacy bump.

Additionality rules are now being drafted for the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism (PACM), also known as Article 6.4. This is one of the mechanisms created by the Paris Agreement that will facilitate an open, global market for carbon credits that properly accounts for credit retirements in national emissions inventories. The PACM is meant to replace and improve upon the CDM and will likely become a new standard for carbon crediting programs, so any further developments on additionality via the PACM could be highly influential for the rest of the market. Financial analysis, barrier analysis, and common practice analysis are all still present, and at this time, it seems unlikely they will change dramatically without significant advocacy efforts.

Categories of CDR

There are many distinct categories of CDR. CDR.fyi offers a helpful classification of specific technological pathways as does the State of CDR report. However, with respect to additionality, I believe there are three relevant categories of CDR projects:

Standalone: Standalone CDR projects are not directly coupled to other industrial operations, do not produce salable co-products, and exist solely for the purpose of generating CDR. Unless they are subsidized, such projects are clearly additional as they would not and cannot exist without some kind of carbon finance. An example is direct air capture (DAC) paired with geologic storage of captured CO2 and no co-production of water, provision of cooling services, enhanced oil recovery, use of waste heat, or generation of low-carbon fuels or chemicals.

Incremental: Incremental CDR projects are directly coupled to other industrial operations but still require additional upfront and/or ongoing investment to be sustained. While the coupled industrial operations could theoretically pay for the removal activities and still be profitable overall, the projects are still additional under the investment analysis test from CDM guidance as they would not be the “The most economically or financially attractive alternative” given that the operations could simply just not pay for incremental CDR activities. Examples include biochar production and application at a farm, mine tailing carbonation, and retrofits for point-source capture and storage of biogenic CO2 generated from ethanol plants (putting debates about system boundaries aside for the moment). In these cases, the farm, mine, and ethanol plant respectively could theoretically pay for the use of their by-products to generate CDR and still have a profitable enterprise overall, but the projects can still be additional given the incremental resources and funds that are required for them to occur.

Incidental: Incidental CDR projects are or can be performed to achieve some end other than CDR, meaning that any removal essentially occurs as an incidental by-product. These projects occur in cases where there is ample economic value via a co-product, which could either be a good or a service. They may already be common practice, but new processes can also fall in this category. Current additionality rules would prevent any of these projects from being able to issue carbon credits. Examples include application of agricultural lime merely for crop benefits in a way that results in enhanced rock weathering (ERW) CDR, use of lime in wastewater treatment plants in a way that results in alkalinity enhancement, and biochar that is profitably applied before carbon finance.

It must be noted that I am only referring here to CDR from anthropogenic activities. These categories do not include removal of CO2 from the atmosphere by nature itself such as through uptake in unmanaged terrestrial and oceanic sinks. This kind of removal is already separately factored into carbon cycle calculations via the airborne fraction, and any projects that seek to protect natural sinks must be treated differently from anthropogenic CDR lest they create confusion and risk of not meeting climate targets. Refer to materials on Geological Net Zero for more on this topic.

Standalone CDR benefits from strict additionality requirements. Incremental CDR should be able to pass most additionality tests given its realistic dependence on carbon finance, although this category faces separate issues related to ongoing system boundary debates and market leakage concerns, as discussed later on.

A key question revolves around whether incidental CDR projects should be permitted to issue credits even though they are likely not additional based on the traditional understanding of the concept. The following sections explore why additionality is ultimately a necessary test for CDR projects but also how it has several issues that must be resolved.

Why Additionality Must Be Maintained

By definition, non-additional removals would occur regardless of their ability to issue carbon credits. Some on the anti-additionality side make the argument that getting rid of additionality requirements would lead to more non-additional removals by way of providing extra incentives to incidental CDR pathways. However, if extra incentives are required to make such removals viable, then they are actually additional and should be able to pass a well-designed additionality test. This means that the debate can reduce to whether additionality tests should be forgone entirely and whether, as an extreme example, an incidental CDR process that is wildly profitable from the sale of its co-products alone should also be able to issue carbon credits.

To protect the already-questionable environmental integrity of most carbon credits, additionality tests should be preserved. More CDR will occur in a world with additionality requirements. There are limited buyer funds, and any use on non-additional, incidental CDR is parasitic toward additional CDR that actually needs these funds to occur. Additionally, as the marginal cost of non-additional CDR is $0/t—although there would still be nominal costs related to monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) as well as marketing and issuance if it were allowed to issue credits—producers of it would have total pricing flexibility. This would create distortions in the CDR market, potentially driving prices down to unsustainable and unscalable levels for low-value removals that would have occurred anyway. Preventing these kinds of issues is a major part of the motivation of additionality requirements in the first place.

As an example, imagine a world where there are one billion tonnes per year of incidental, non-additional CDR. If there are no additionality requirements, assume these tonnes could be profitably sold for $10 each to cover the costs of MRV and issuance that would not need to occur otherwise. Also assume there is an uncapped amount of standalone CDR tonnes that can be generated for $100/t. If there is $10B per year worth of demand in the world with CDR purchasing, then having additionality requirements results in an extra 100M tonnes of standalone CDR relative to the case without additionality. The table below walks through this logic. While no formal MRV occurs to prove out the incidental tonnes in the baseline scenario or the world without additionality, the removals are still occurring.

This is the core logic behind additionality requirements. There is a fundamental belief, and good reasoning, backing the idea that such requirements result in improved environmental benefits relative to not having them. Basic rationality dictates that one should not consider an equivalent attribute when comparing two options and only focus on the marginal differences between them. E.g., if job A and job B both pay $100K per year, then it does not make sense to evaluate the salary on a standalone basis for either job. The focus should only be on the marginal differences between them.

At a conceptual level, additionality requirements are environmentally sound. However, there are several issues, some of them unique to CDR, that must be addressed and resolved for the tests to function fairly and as intended.

Issues to Resolve

Removals vs. Reductions

As noted in the introduction, emissions reductions and removals are fundamentally different. Reductions represent not emitting whereas removals represent the active extraction of CO2 from the atmosphere. The benefit from a non-additional reduction simply flows to the party that was responsible for it; they were emitting, and now they’re not. Removals are more complicated, as a non-additional removal still represents a real, physical flux that could still theoretically compensate for a positive emission somewhere else.

Imagine a world with only two companies, A and B. Both emit 10 tonnes per year for a total of 20 tonnes added to the atmosphere. Company A makes a profitable change to their process and now emits zero tonnes and removes 10 tonnes for a total of –10 tonnes per year, while company B makes no change and still emits 10 tonnes. At this point, from an atmospheric perspective, company A’s 10 tonnes net removed cancel out company B’s 10 tonnes emitted for a system-wide total of zero tonnes. However, as company A’s action is non-additional given its profitability, they are unable to trade the credit, leaving company B on the hook for their emissions despite the system being at net-zero emissions.

This is certainly an interesting accounting issue for those who defend removal additionality, although it may not actually manifest for a few reasons. One of these is that incidental removals are often integrated into larger, net-emitting systems. Generally, to be profitable without the sale of carbon credits, there needs to be some good or service provided by incidental CDR processes, such as biochar use in crops or lime in wastewater treatment plants. In these cases, it is unlikely that the underlying systems currently or will soon have net-zero emissions, meaning the removal benefit can simply be applied against the emissions of the process. For example, if biochar is applied in a profitable manner to a farm, any carbon removal associated with the application could be quantified and applied against the broader emissions of the crops produced by that farm.

There may be cases where this breaks down and the integrated process has net-negative emissions. One example could be a process that links ERW with phytomining of the resulting crops to produce nickel (see Metalplant). Theoretically, this process could involve incidental CDR due to revenues from nickel sales and process-wide net-negative emissions if there is more CDR than process emissions. It is a bit absurd that additionality requirements result in this process simply sitting on its real, net negativity, especially when there are others willing to pay for it, but there is no apparent way to allow crediting in this case without abandoning additionality requirements and dealing with the consequences.

To mitigate the absurdity and create a fairer playing field for non-additional removals, a compromise could be allowing such CDR to be inset. Insetting is a relatively new and spongy term, but it generally refers to actions that companies take to reduce emissions in their own supply chains. In this context, insetting would allow a buyer of a product with net-negative emissions from incidental removals to incorporate and claim those removals in their own product systems. This occurs at the facility-level in the prior biochar example, but the nickel case is more interesting in that carbon-negative nickel could then be used by a battery company, for example, in a way that fairly compensates for other emissions from battery manufacturing.

Alternatively, the crediting benefit could perhaps be claimed by an entity that buys nickel but perhaps not this specific, carbon-negative nickel in a novel book-and-claim approach that still maintains integrity while not threatening the broader credit market. Using one of these strategies would allow the removals to be used and even monetized rather than just “floating” in space.

There may still be cases where there are non-additional tonnes without meaningful insetting opportunities, such as a wastewater treatment plant that decarbonizes through traditional means but still applies lime in a profitable way that results in alkalinity enhancement and net carbon removal. In these cases, we may just have to accept that these removals will not have separate monetization opportunities and that they will ultimately contribute to sustaining net-negative emissions in a no-cost manner.

Co-Product Pricing Variation

Additionality is often assessed during initial project validation. Validation occurs prior to ongoing verification and credit issuance, and it is generally required to get a project listed on a registry and eligible to generate credits. However, additionality can be a moving target. A project may look profitable or unprofitable on paper without carbon finance at the beginning of a project, but this determination could change due to fluctuating co-product prices.

With additionality rules in place, projects that are non-additional today cannot get validated. If the situation changes due to variable co-product pricing, they could file for validation at that point. Projects that are additional today but become non-additional during the course of the project could be allowed to slide until the end of their crediting period (which is usually only five or ten years), and their new non-additional state would simply prohibit them from being able to renew their validation. Additionality could also be assessed on an ongoing basis as part of each verification cycle, although this determination could become murky as time goes on and the project gets further away from its initial investment.

Additionality rules could also be slightly loosened to allow for cases with highly variable co-product revenue. E.g., if it can be sufficiently proven by project developers during validation that direct biochar sales prices or monetary benefits from agricultural liming are variable enough that carbon finance is needed to reliably and confidently support the project, then additionality should be satisfied. This analysis could be performed and justified as part of sensitivity analysis in an investment analysis additionality test. If volatile co-product revenues could make the project additional or create issues with investors, then it is entirely reasonable to allow such projects to pass the test, although the burden of adequately proving this will rest on the developer.

Artificial Cost and Barrier Inflation

Another potential issue associated with additionality tests is the creation of incentives to falsely or unnecessarily inflate costs or the significance of other barriers simply to satisfy the requirement. In this case, it may actually be more profitable to unnecessarily purchase more expensive equipment to make the project additional and therefore able to tap into carbon credit sales.

Imagine a simplified incidental CDR process that produces one tonne of CDR and one unit of a co-product that is worth $100. If the overall cost of this process is $80, then the associated removal is not additional and therefore cannot be monetized. However, the project developer could choose to use more expensive equipment and artificially boost the salaries of plant operators, resulting in a new process cost of $120. Now, the process would not be economically viable without the sale of credits, making them additional. If the associated tonne could be sold for $200, then the new project developer’s profit is $200 (for the CDR) plus $100 (for the co-product) minus $120, which equals $180, nine times higher than the original profit of $100 – $80 = $20.

There are a couple of ways to address this. The first would be applying a reasonableness test to cost assumptions during the additionality assessment. Are the stated costs and barriers reasonable and customary for this project? Is anything dramatically out of the ordinary? While this process increases the effort required for validation, evaluating the answers to such questions would add a check against cost or barrier inflation. In addition, additionality standards could be somewhat loosened for edge cases where there is a reasonable chance that small differences in costs or barriers could result in a change to the project’s additionality. This would mitigate the incentive for developers to do this on the margins and limit the evaluation to more extreme cases.

This is similar to the co-product price volatility issue but on the cost side; if the project is close to being additional, it probably needs carbon finance to realistically operate and scale and therefore should be allowable. Additionality cut-offs should target projects that very clearly will move forward without carbon credit support.

Additionality of Emitting Systems

There are cases where an incremental CDR process might be additional but result in broader system-wide changes that result in more emissions, rather than fewer, relative to the baseline scenario, even with the CDR included. For such projects, carbon finance is additional for more than just the CDR project by incentivizing broader emitting systems to open or stay open.

For example, consider a mine that is on the verge of bankruptcy. The mine emits 100,000 tonnes of CO2 per year but produces tailings that can be used in an incremental CDR process that removes 10,000 tonnes per year. The CDR here would be additional as it requires additional costs that without carbon finance would not be the most economically attractive option for the mine. However, in this case, the profits from the sale of CDR credits could be just enough to keep the mine open when it would otherwise close. At the system level, allowing this process to cash in on the CDR revenues risks resulting in 100,000 – 10,000 = 90,000 more tonnes of CO2 being emitted per year despite the CDR process itself being additional.

This demonstrates that additionality tests are necessary but not sufficient for ensuring desired environmental outcomes. In this case, market leakage considerations, which is another area commonly explored in carbon crediting programs and standards, would need to be used to disqualify the project.

The Future of Additionality and CDR

Additionality is an issue that goes far beyond carbon credits. Many philanthropic, business, and government-funded programs face similar additionality questions: would this have still happened if we didn’t fund it? Would people or companies still engage in certain actions even without subsidies? Would people still have bought our product without this advertising campaign? How do we really calculate the marginal impacts of investments relative to baselines?

In some ways, these assessments are easier from carbon credits than programs in other domains as we are dealing with discrete projects that have somewhat well-defined boundaries and exist pretty firmly in industrial contexts. While there is certainly complexity associated with the examples discussed throughout this article, it is nowhere near the level of difficulty that program evaluation policy professionals must deal with in a myriad of other contexts from housing policy to public health campaigns to marketing. For CDR, if we start to be a bit more lenient with edge cases as I recommend here, then it should be pretty apparent to a reasonable observer whether a process is additional or not. And for non-additional projects, there should still be relatively straightforward ways to take credit for the removal in the integrated process or via insetting or book-and-claim approaches.

None of this is to say that we should not find ways outside of carbon credits to support non-additional CDR. In fact, the opposite is true. Pay-for-practice regimes, other kinds of subsidies, new regulations, contribution claims, smarter insetting, new book-and-claim guidance, updated corporate and national carbon accounting systems, and other ways to support industrial integration of CDR all hold tremendous promise for helping create climate benefits outside of a pure-play carbon credit context. These opportunities can all still enable use of carbon-negative claims, just within their corresponding supply chains and in a way that does not threaten the integrity of flexibly traded carbon credits.

Strict additionality rules only really need to apply for carbon credits to protect the sanctity of compensatory claims and create more removal for a limited amount of credit demand. Maintaining additionality also allows for more consistent rules in carbon crediting programs and standards that allow for a more harmonious and integrated system across voluntary and compliance markets for both reductions and removals. By making a few tweaks to additionality tests and looking for new opportunities for non-additional removals, we can have all kinds of CDR pathways work in harmony to accelerate our path toward net negativity.